Potential theory

Contents

6.6. Potential theory#

Complex analysis is a useful lens through which to view much of approximation theory, particularly when it comes to spectral methods.

The error in polynomial interpolation includes the factor

where the \(x_j\) are the interpolation nodes. Taking the log of the modulus yields

This motivates us to define

which is harmonic in the complex plane except at the \(x_j\). There is a compelling physical interpretation of \(\phi_N\) as the electrostatic potential due to point charges in the plane. (A point charge in the plane corresponds to a line of charge in 3D space, which turns the electrostatic force into \(O(|z-x_j|^{-1}\)).)

Things get interesting in the limit \(N\to \infty\). The point charges on \([-1,1]\) become a charge density \(\rho(x)\). If we normalize \(\int_{-1}^1 \rho(x)\, dx\) to be 1, then

is the fraction of the nodes that lies in the subinterval \([a,b]\). For equispaced points, \(\rho(x)=\tfrac{1}{2}\). For Chebyshev points,

Key theorem#

The potential due to a charge density \(\rho\) is

Theorem 6.6.1 (Polynomial potential theory)

Suppose that sets of \(N\) interpolation points \(\{x_j\}\) are given that converge to density function \(\rho(x)\) as \(N\to \infty\). Define the potential \(\phi\) as above, and let

Suppose a function \(u\) is analytic throughout the region

where \(\phi_u > M\) is a constant, and let \(p_N\) be the polynomial that interpolates \(u\) at the \(\{x_j\}\) for that \(N\). Then there exists a constant \(C>0\) such that

for all \(x\in[-1,1]\) and all \(N>0\). The same estimate holds, for a different constant \(C\), for any derivative, \(|u^{(d)}(x) - p_N^{(d)}(x)|\).

The theorem promises exponential/geometric convergence over \([-1,1]\) as a function of \(N\), provided \(u\) is analytic throughout some region in \(\mathbb{C}\) that contains the interval.

p10: polynomials and corresponding equipotential curves#

using Polynomials

N = 16

data = [

(@. -1 + 2*(0:N)/N, "equispaced points"),

(@. cospi((0:N)/N), "Chebyshev points"),

]

xx = -1:0.005:1

xc = -1.4:0.02:1.4

yc = -1.12:0.02:1.12

results = []

for (i,(x,label)) in enumerate(data)

p = fromroots(x)

pp = p.(xx)

pz = [p(x + 1im*y) for x in xc, y in yc]

push!(results, (;x,pp,pz,label))

end

using CairoMakie

fig = Figure()

levels = 10.0 .^ (-4:0)

for (i,r) in enumerate(results)

Axis(fig[i, 1], xticks=-1:0.5:1, title=r.label)

scatter!(r.x, zero(r.x))

lines!(xx, r.pp)

Axis(fig[i, 2], xticks=-1:0.5:1, title=r.label)

scatter!(r.x, zero(r.x))

contour!(xc, yc, abs.(r.pz); levels, color=:black)

limits!(-1.4, 1.4, -1.12, 1.12)

end

fig

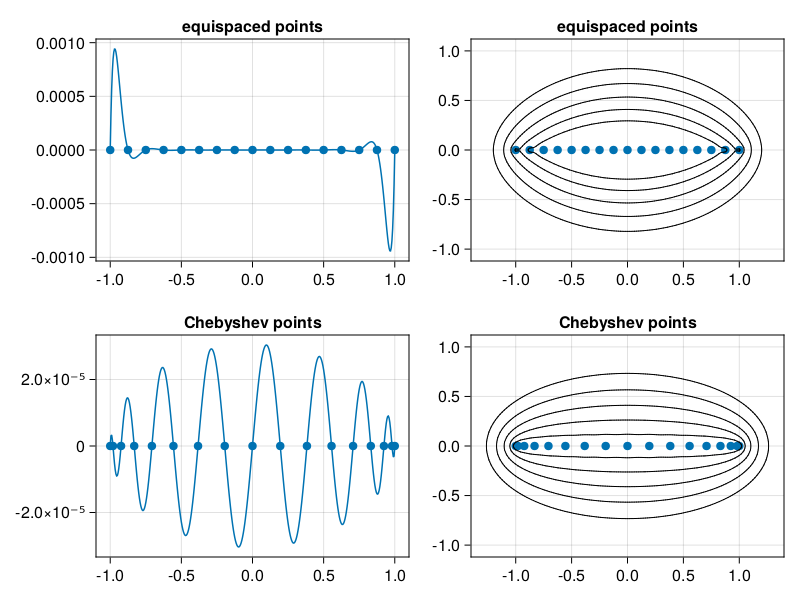

The left column of plots shows \(\Phi(x)\), while the right column shows the level curves of \(\phi\), for both equispaced and Chebyshev points.

Equispaced points#

A little elbow grease shows that

In particular, \(\phi(0)=-1\) and \(\phi(\pm1) = -1 + \log 2\). Since \(|\Phi(x)|\approx \exp\bigl(N\phi(x)\bigr)\), we find that

Furthermore, the smallest contour curve of \(\phi\) that contains \([-1,1]\) also contains a significant additional part of the complex plane, requiring “hidden” analyticity for \(u\) beyond the interval itself. The Runge function \(1/(1+16x^2)\), for example, has poles at \(\pm \frac{1}{4}i\), and any equipotential curve that avoids including these will also exclude the ends of the interval.

Chebyshev points#

For 2nd-kind Chebyshev points,

(One has to be careful about how to choose the branch of the square root above.) Remarkably, the interval \([-1,1]\) itself is an equipotential curve for this \(\phi\). More generally, if

for \(r > 1\), then \(\phi(z) = \log(r/2)\). This places \(z\) on the ellipse with foci at \(\pm 1\), major axis \(r+r^{-1}\), and minor axis \(r-r^{-1}\). We call this the Bernstein ellipse \(E_r\).

Theorem 6.6.2 (Accuracy of approximation on Chebyshev points)

Suppose \(u\) is analytic on and inside the Bernstein ellipse \(E_r\), let \(d\ge 0\) be an integer, and let \(w_i\) be the \(d\)th Chebyshev spectral derivative of \(u\) on the Chebyshev grid. Then

We close by noting that the Chebyshev points are not the only ones that allow well-conditioned interpolation. More generally, roots of Jacobi polynomials all have similar density near \(x=\pm 1\), which is the critical property. What distinguishes the Chebyshev case is that the points are known in closed form, and they allow a deep connection to Fourier methods, as we will see.