6. Linearization¶

A pendulum with length \(L\) and angle of deflection \(\theta(t)\) from the vertical is governed by the nonlinear second-order equation

where \(g\) is gravitational acceleration. It’s standard to argue that as long as \(|\theta|\) remains small, a good approximation is the linear problem

because \(\sin \theta \approx \theta\). We want to get more systematic with this process.

First note that we can recast the nonlinear second-order problem as a first-order system in two variables, just as we did for linear equations. Define \(x=\theta\) and \(y=\theta'\). Then

This trick works for any nonlinear second-order equation \(\theta''=g(t,\theta,\theta')\). Thus we can focus on problems in the general form

As we did with single scalar equations, we will pay close attention to steady states or fixed points of these systems. Here this means finding constants \((\hat{x},\hat{y})\) such that

For the nonlinear pendulum, both \((0,0)\) (straight down, at rest) and \((\pi,0)\) (straight up, at rest) are steady states.

We are interested in the stability of fixed points, i.e., the dynamics close to them. We will use linear approximations of the functions \(F\) and \(G\) near a fixed point:

where it is understood for brevity that the partial derivatives are all evaluated at \((\hat{x},\hat{y})\). Given that \((\hat{x},\hat{y})\) is a fixed point, \(F(\hat{x},\hat{y})=G(\hat{x},\hat{y})=0\).

Now define

Then

This inspires the following definition.

The Jacobian matrix of the system \(x'=F(x,y),\, y'=G(x,y)\) is

The Jacobian matrix is essentially the derivative of a 2D vector field. As such, it is also a function of the variables \(x\) and \(y\).

6.1. Stability¶

Let’s summarize. In the neighborhood of a fixed point \((\hat{x},\hat{y})\), we can define the deviation from equilibrium by the variables \(u_1(t)=x(t)-\hat{x}\), \(u_2(t)=y(t)-\hat{y}\). These variables approximately satisfy \(\mathbf{u}'=\mathbf{J}(\hat{x},\hat{y})\mathbf{u}\), which is a linear, constant-coefficient system in two dimensions. Thus, near a steady state, dynamics are mostly linear.

We are now right back into the phase plane we studied earlier. In particular:

The stability of a steady state is (usually) determined by the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix at the steady state.

Example

Let’s examine the steady states of a pendulum with damping,

with \(\gamma > 0\). It transforms into the first-order system

These define \(F(x,y)\) and \(G(x,y)\). From here we note all the first partial derivatives:

The first steady state we consider is at the origin. Here the Jacobian matrix is

The eigenvalues are roots of \(\lambda^2 +\gamma \lambda + \frac{g}{L}\), the same as a linear oscillator with \(\omega_0 = \sqrt{g/L}\) and \(Z = \gamma/2\omega_0\). If \(Z<1\), we get a stable spiral. If \(Z\ge 1\), we get a stable node. This all agrees well with our experience with a pendulum hanging straight down.

The other steady state is at \((\pi,0)\). Now the Jacobian is

with characteristic polynomial \(\lambda^2 + \gamma \lambda - \frac{g}{L}\). The eigenvalues are

It’s obvious that \(\lambda_2 < 0\). Since \(\gamma^2+\frac{4g}{L} > \gamma^2\), it follows that \(\lambda_1 > 0\). Hence this equilibrium is a saddle point.

The caveat on using eigenvalues for stability is when they both have zero real part, which is weakly stable in the linear sense. In such cases the details of the nonlinear terms of the system can swing the stability either way.

Example

The system

is called a predator–prey equation. If species \(y\) is set to zero, species \(x\) would grow exponentially on its own (the prey). Similarly, species \(y\) would die off on its own (predator). We assume that encounters between the species are jointly proportional to the population of each, and they subtract from the prey and add to the predators.

We find fixed points when \(3x-(x y/2)=(x y/4)-y=0\), which has two solutions, \((0,0)\) and \((4,6)\). The Jacobian matrix of the system is

At the origin, the Jacobian becomes

The eigenvalues of a diagonal matrix (in fact, any triangular matrix) are the diagonal entries. Hence the origin is a saddle point.

At the other steady state we have

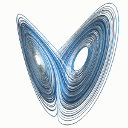

The characteristic polynomial is \(\lambda^2 + 3\), so the eigenvalues are \(\pm i\sqrt{3}\). Close to the point, the orbits are impossible to tell apart from those of a linear center:

However, as we zoom out, the nonlinearity of the system makes its influence felt:

For a different system, however, the nonlinearity could cause this point to be asymptotically stable or unstable.